Image: Photo by Xiaoqi Feng, Author provided

One in four Australian adults feel lonely, and the impacts can be dire. Loneliness increases our risks of depression, diabetes, dementia, self-harm and suicide. But likening it to a disease and proposals to treat it with a pill miss the point: we’ve been building for loneliness over many decades and decision-makers have been asleep at the wheel.

Having studied the issue, we view loneliness as largely a product of our environment – what we call a “lonelygenic environment” – not a disease or a problem with any particular individual. So what is this “lonelygenic environment”?

Over decades, our cities have become sprawling low-density agglomerations. Many places are too far to walk from home. Short errands are routinely done by car, erasing opportunities to stop and chat with locals.

Large-scale felling of street trees has not only obliterated natural shade, but severed our connection with the “more than human” world. Car traffic dominates residential roads, which are also clogged with parked cars.

We have lost the people-friendly streets that we once used for regularly gathering, playing and celebrating with neighbours. No wonder we now know so few by name.

Read more: We’re at a fork in the road: do we choose neighbourhoods to live, work and play in?

If the determinants of loneliness are largely environmental, so too must be the solutions. Yet we hear so little about this.

How much difference can green space make?

In a previous Conversation article, we suggested investing in public green space is part of the solution to the epidemic of loneliness. The article was based on our longitudinal study that reported a greening target of 30% local landcover could cut the odds of becoming lonely by a quarter. Among people living alone, who tend to be more vulnerable to loneliness, green space cut those odds by up to a half.

Should we be ‘prescribing’ nature?

People’s odds of loneliness could fall by up to half if cities hit 30% green space targetshttps://t.co/9o3Uo8mx5t

@ThomasAB2020 @feng_xiaoqi #socialdeterminantsofhealth

— Australian Urban Observatory (@RMITAUO) June 10, 2021

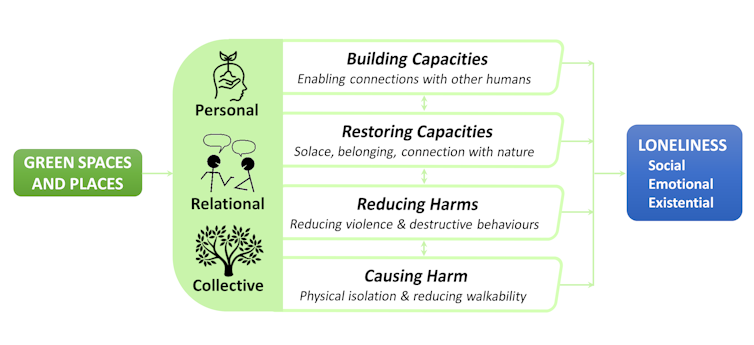

Our review identified multiple pathways for reducing loneliness. These included:

- building capacities for connection with community

- restoring our sense of belonging and connection with nature

- reducing harms, such as violence, that may otherwise lead to loneliness.

The quality of the green space matters

During the COVID-19 pandemic we undertook a nationally representative survey and found the odds of connecting with neighbours were five times higher for people who visited high-quality green space than for those who didn’t or couldn’t.

Related benefits were also much stronger if green spaces were higher quality. For example, exercise and relief from stress were both more commonly reported by people visiting higher-quality green spaces.

Quality was defined by participants’ views on things such as access, aesthetics, facilities, incivilities (e.g. litter, disrepair) and safety. Perceptions are important because the qualities of a green space need to resonate for people to visit them.

Regular visits to green spaces foster attachment and belonging. These spaces permit quiet contemplation in solitude, but also bring people together and connect people with nature. They become revered as settings for gatherings, bonding, cheering and shared memory-making.

Read more: Why do we find making new friends so hard as adults?

By encouraging relaxation and playfulness – which can be frowned upon in other settings – green spaces may also enable connection for people who otherwise find it difficult, such as those with highly introverted personalities.

The psychologically restorative benefits of green space are now well-documented. Green spaces such as healing gardens can serve as therapeutic landscapes, offering refuge and respite for those experiencing loneliness, which can stem from some form of trauma. While usually provided for patients, these settings might also offer sanctuaries for health professionals experiencing burnout.

Read more: Lonely after lockdown? How COVID may leave us with fewer friends if we are not careful

The bottom line is that higher-quality green space maximises opportunities for both social connection and health. While our previous research and other studies highlight inequities in access to green space, we must pay even more attention to inequities in the quality of green space.

Consult communities to get it right

This may all sound like we think the impacts of green space are universally positive; we don’t. For instance, many studies in countries such as Denmark, Poland and New Zealand report that some people with disabilities, who are already vulnerable to loneliness, face significant barriers to visiting green spaces and may feel “out of place” within them.

Other research indicates that the creation or regeneration of green spaces in communities may be associated with disempowerment and dispossession, by making nearby housing less affordable.

In other words, a nearby green space that is highly attractive and a source of joy for some people may for others be a symbol of processes that aggravate loneliness and perpetuate misery.

That is why community views on the design of green space really matter. Consultation is key to ensure everyone feels meaningfully engaged in the process.

Our program of work, and our new review in particular, shows green space qualities depend on the context, preferences and needs of local residents. It is clear we need local networks of green spaces that provide something of value for everyone.

Finally, the process of urban greening itself can help counter loneliness by empowering communities to actively participate in creating and maintaining local green spaces. This has been done successfully over decades by the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney’s Community Greening program. By bringing people together to create green spaces, the garden has been quietly showing us the solution to our lonelygenic environment all along.

This article was co-written by:

Disclosure statement

Xiaoqi Feng works for the University of New South Wales and has received research funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the National Heart Foundation of Australia, and Hort Innovation Ltd.

Thomas Astell-Burt works for the University of Wollongong and has received research funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the National Heart Foundation of Australia, and Hort Innovation Ltd.