Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

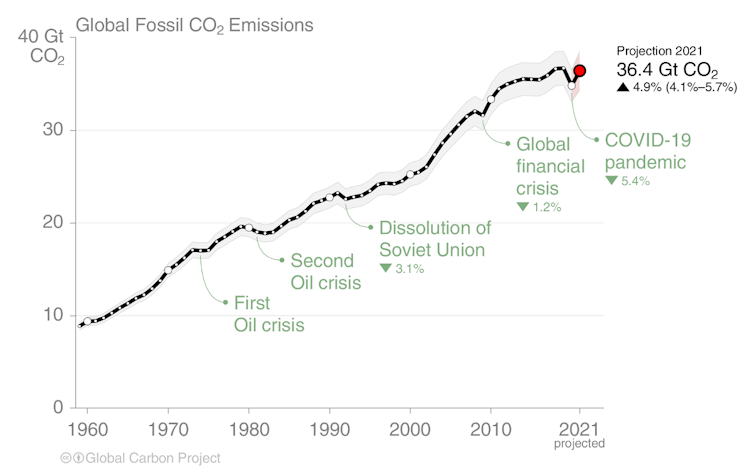

Global carbon dioxide emissions have bounced back after COVID-19 restrictions and are likely to reach close to pre-pandemic levels this year, our analysis released today has found.

The troubling finding comes as the COP26 climate talks continue in Glasgow in a last-ditch bid to keep dangerous global warming at bay. The analysis was undertaken by the Global Carbon Project, a consortium of scientists from around the world who produce, collect and analyse global greenhouse gas information.

The fast recovery in CO₂ emissions, following last year’s sharp drop, should come as no surprise. The world’s strong economic rebound has created a surge in demand for energy, and the global energy system is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

Most concerning is the long-term upward trends of CO₂ emissions from oil and gas, and this year’s growth in coal emissions, which together are far from trending towards net-zero by 2050.

The global emissions picture

Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels dropped by 5.4% in 2020, compared to the previous year. But they are set to increase by about 4.9% above 2020 levels this year, reaching 36.4 billion tonnes. This brings them almost back to 2019 levels.

We can expect another 2.9 billion tonnes of CO₂ emissions this year from the net effect of everything we do to the land, including deforestation, degradation and re-vegetation.

This brings us to a total of 39.4 billion tonnes of CO₂ to be emitted by the end of this year.

The fast growth in emissions matches the corresponding large increase in energy demand as the global economy opens up, with the help of US$17.2 trillion in economic stimulus packages around the world.

CO₂ emissions from all fossil fuel types (coal, oil and natural gas) grew this year, with emissions from coal and natural gas set to grow more in 2021 than they fell in 2020.

Emissions from global coal use were declining before the pandemic hit in early 2020 but they surged back this year. Emissions from global gas use have returned to the rising trend seen before the pandemic.

CO₂ emissions from global oil use remain well below pre-pandemic levels but are expected to increase in coming years as road transport and aviation recover from COVID-related restrictions.

Nations leading the emissions charge

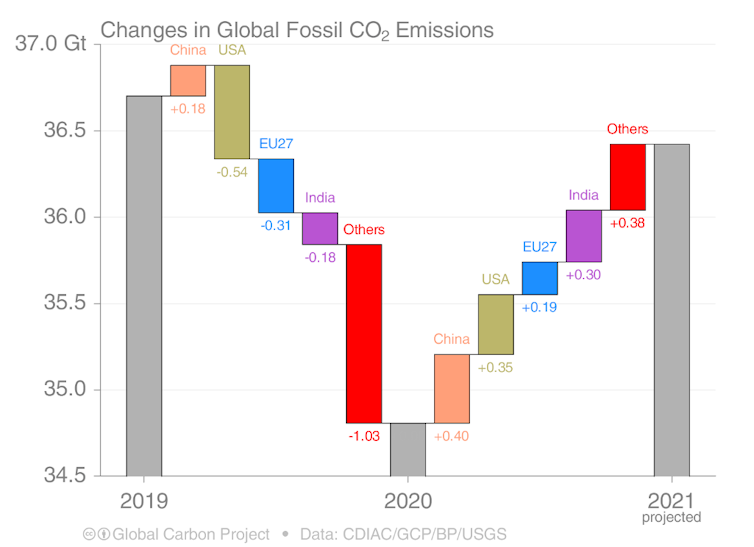

Emissions from China have recovered faster than other countries. It’s among the few countries where emissions grew in 2020 (by 1.4%) followed by a projected growth of 4% this year.

Taking these two years together, CO₂ emissions from China in 2021 are projected to be 5.5% above 2019 levels, reaching 11.1 billion tonnes. China accounted for 31% of global emissions in 2020.

Coal emissions in China are estimated to grow by 2.4% this year. If realised, it would match what was thought to be China’s peak coal emissions in 2013.

India’s CO₂ emissions are projected to grow even faster than China’s this year at 12.6%, after a 7.3% fall last year. Emissions this year are set to be 4.4% above 2019 levels – reaching 2.7 billion tonnes. India accounted for 7% of global emissions in 2020.

Emissions from both the US and European Union are projected to rise 7.6% this year. It would lead to emissions that are, respectively, 3.7% and 4.2% below 2019 levels.

US and EU, respectively, accounted for 14% and 7% of global emissions in 2020.

Emissions in the rest of the world (including all international transport, particularly aviation) are projected to rise 2.9% this year, but remain 4.2% below 2019 levels. Together, these countries represent 59% of global emissions.

The remaining carbon budget

The relatively large changes in annual emissions over the past two years have had no discernible effect in the speed at which CO₂ accumulates in the atmosphere.

CO₂ concentrations, and associated global warming, are driven by the accumulation of greenhouse gases – particularly CO₂ – since the beginning of the industrial era. This accumulation has accelerated in recent decades.

To stop further global warming, global CO₂ emissions must stop or reach net-zero – the latter meaning that any remaining CO₂ emissions would have to be compensated for by removing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

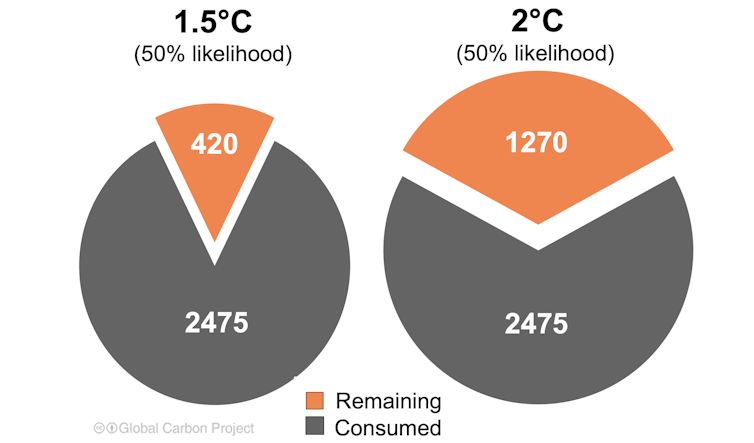

Carbon budgets are a useful way of measuring how much CO₂ can be emitted for a given level of global warming. In our latest analysis, we updated the carbon budget outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in August this year.

From the beginning of 2022, the world can emit an additional 420 billion tonnes of CO₂ to limit global warming to 1.5℃, or 11 years of emissions at this year’s rate.

To limit global warming to 2℃, the world can emit an additional 1,270 billion tonnes of CO₂ – or 32 years of emissions at the current rate.

These budgets are the compass to net-zero emissions. Consistent with the pledge by many countries to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, CO₂ emissions need to decline by 1.4 billion tonnes each year, on average.

This is an amount comparable to the drop during 2020, of 1.9 billion tonnes. This fact highlights the extraordinary challenge ahead and the need to increase short- and long-term commitments to drive down global emissions.

This article was the result of a collaboration between:

Disclosure statement

Pep Canadell receives funding from the Australian National Environmental Science Program – Climate Systems Hub.

Corinne Le Quéré receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement Nos. 821003 (4C) and 776810 (VERIFY), from the UN Natural Environment Research Council under grant NE/P021417/1 (SONATA) and NE/V011103/1 (Frontiers), and from the UK Royal Society under grant RPR1191063 (Research Professorship.

Glen Peters receives funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement Nos. 821003 (4C), 776810 (VERIFY), 820846 (PARIS REINFORCE), and 958927 (CoCO2).

Pierre Friedlingstein receives funding from the European Commission Horizon 2020 (H2020) 4C project.

Robbie Andrew receives funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement Nos. 821003 (4C), 776810 (VERIFY), and 958927 (CoCO2).

Rob Jackson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.