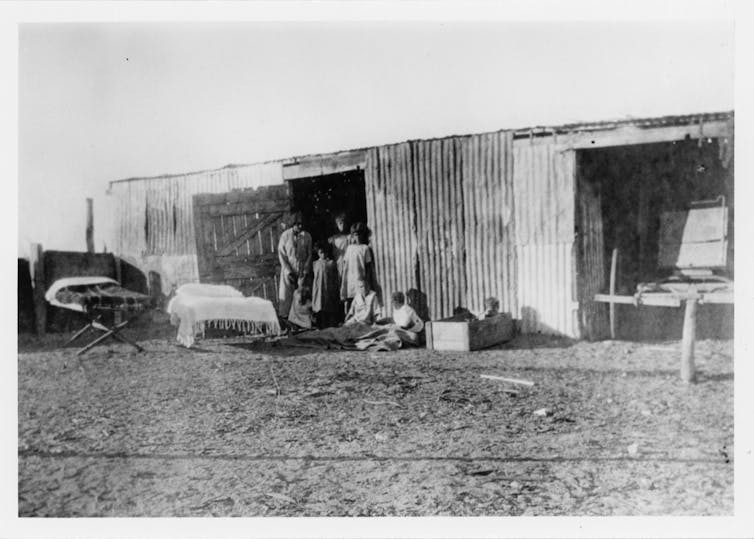

Missionary Annie Lock with Enbarda (Betsy) left, and Dolly Cumming, both children from the Alice Springs area in Central Australia. Photo taken in Darwin. National Archives of Australia

Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander readers are advised this story contains images of people who have died.

“We have fared well out of native hands”, wrote missionary Annie Lock from Oodnadatta in South Australia in 1924. Four years later, having moved to Harding Soak north of Alice Springs, she declared the government should “give the natives food in place of their country”.

Lock’s recognition that white Australians had taken Aboriginal land and owed them compensation was ahead of her time, even if her idea of appropriate compensation was inadequate.

Born in 1876 into a Methodist sharefarming family of 14 children in South Australia’s Gilbert Valley, Lock was a practical woman with a very basic education. A dressmaker by trade, in 1903 she joined what would become the United Aborigines Mission.

It operated on faith lines: missionaries were unpaid and could not actively solicit donations, relying on prayer to answer all needs. Lock, like her colleagues, developed a nice line in inviting supporters to “join her in prayer” for very specific needs, such as “a nice staunch horse for £12”, hoping for a “practical” show of sympathy.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Mary Jane Cain, land rights activist, matriarch and community builder

From 1903 to 1937, she lived in 10 mission camps across four states and territories. Renowned for being the “Big Boss”, she usually worked alone establishing “new work” — partly because her colleagues found her intensely uncollegial.

She wasn’t only out of step with many of her contemporaries in her belief Aboriginal Australians deserved compensation: she also believed Aboriginal people had a future and they could be “useful citizens” of Australia.

Once again, however, her view of their place in broader Australian society was narrow. She did not imagine Indigenous doctors, lawyers or politicians, but labourers, stockmen and domestic servants.

I first encountered Annie Lock through some of her letters in the South Australian archives. She berated government officials, demanding action and funding for (what she saw as) Aboriginal people’s interests. She was bolshie and outspoken.

At the time I was a young graduate student and naively thought I had uncovered a feminist heroine. I was quickly disabused: for all her intrepid and gutsy behaviour, Lock held intensely socially conservative views in line with her religious conviction.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Elsie Masson, photographer, writer, intrepid traveller

A grand adventure

Lock’s life was like a “girls’ own” adventure story – albeit a teetotal and highly moralistic one.

She made epic horse and buggy journeys across the desert, camped in the middle of nowhere with few resources and was shipwrecked in a pearling lugger. She railed against white men’s abuse of Aboriginal women, and she “rode rough-shod over rules and regulations, always managing to come out on top”, in the words of her obituary from her longsuffering mission society.

Many white Australians felt she went too far. She cuddled Aboriginal children, nursed the sick, and shared her campfire – even “drinking tea out of the same cup”.

After the 1928 Coniston Massacre, in which a police party killed over 100 Aboriginal men, women and children in Central Australia, the Board of Enquiry, widely considered as a whitewash at the time, blamed the unrest leading to the events partly on “a woman missionary living among naked blacks, lowering their respect for whites”.

It was no coincidence that Lock was also one of the people who had publicised the massacre, forcing an enquiry in the first place, after Aboriginal people sought refuge in her camp and told her their horrifying tale.

In fact, rather than “lowering their respect” as a white woman living with Aboriginal people, Lock maintained her camp was an area of mutual respect and negotiation:

They told me their laws; […] I made my rules; they kept them; I kept theirs; we had no trouble.

At certain moments when researching her life, I found Lock seemed impressively broadminded. However, given the uneven distribution of power, the reality was not so idyllic.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

A troublesome woman

Lock was an integral part of the colonial machine, with all its patronising ethnocentricity. As a white woman, Lock was never troubled by any sense that Aboriginal people were her equals.

She could be dictatorial and bloody-minded, with a highly developed sense of what she saw as right and wrong, approving harsh punishment for transgressors. At the Coniston enquiry itself she was critical of those Aboriginal men who killed cattle, suggesting “a good flogging” was called for.

In Western Australia, she actively took children from their families and she was instrumental in establishing Carrolup Native Settlement in 1915 — a forerunner of notorious Moore River Settlement — to which Aboriginal people were removed.

In South Australia in 1924, she started what became Colebrook Home, in which Aboriginal children of mixed descent were institutionalised.

At Ooldea, when Lock was 58, the overworked and tired missionary let her guard slip. An Aboriginal man hit her after she punished his daughter. The daughter should be sent to Colebrook, she suggested, “to punish” him — deviating from the usual missionary script of “in the child’s best interests”.

But history is complicated. One elderly Aboriginal woman smiled when she told an interviewer her memories of Lock, “a real fat one”, playing rounders at Ooldea. The image of a stout middle-aged missionary hitching up her skirts and charging around the sandhills with a bunch of Aboriginal kids is hard to beat.

In Central Australia, some remembered her as a caring for children “on country”, saving them from being sent away.

Lock was consistently vocal about Aboriginal girls’ rights to be protected from white men (although she condoned Aboriginal men’s violent “punishment” of their wives). And while she was irrepressibly evangelistic, she eventually learned Christianity could work with some aspects of Aboriginal culture. Sometimes, she wrote, Aboriginal people could “teach white people a lesson”. They were “real socialist”, sharing the clothes that she gave them. She waxed lyrical about their “corroboree songs” and appreciated the authority of elder generations over the younger.

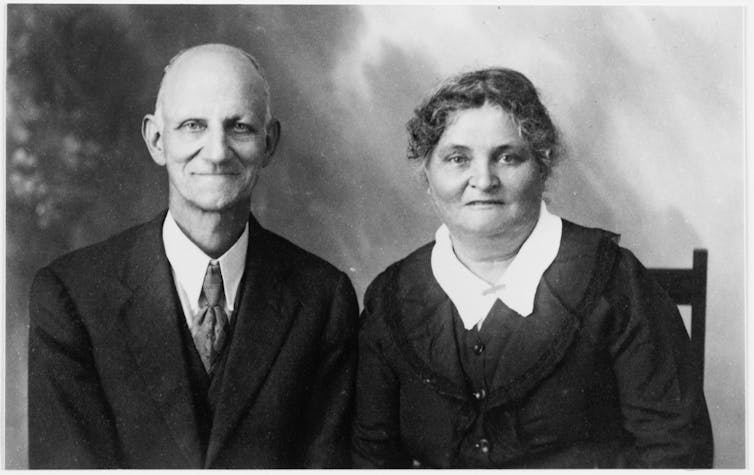

In 1937, aged 60 and after 35 years in the mission field, Lock suddenly retired. Certainly she had been finding her “pioneering” missionary work more of a strain, and her health had suffered, but also, she told her supporters, God was giving her a “quieter work”. Much to everyone’s amazement, this independent woman had found herself a husband.

She married a retired bank manager and spent the last six years of her life evangelising in a caravan around Eyre Peninsula.

Contradictions

In uncovering the life of Annie Lock, I found a woman who was both fascinating and discomfiting. We can try and judge her motivations and actions as an individual of her time, but we cannot ignore her impact.

She saved people’s lives by providing food and healthcare, and a refuge from more hostile forces. She also destroyed families by removing children. She introduced Christianity, which some found a welcome way of navigating the changing world. She was one of an army of “do-gooders” whose haphazard attempts to improve the lives of Aboriginal people did not always have the result that anyone would have desired.

Her personal impact could be positive – some remember her as “lovely” and “motherly”. But her impact as an active participant in “protectionist” government policies, which limited Aboriginal people’s lives and movement and tore families apart, was traumatic and has endured.

This article was written by:

Disclosure statement

Catherine Bishop receives funding from the Australian Research Council as a DECRA Research Fellow at Macquarie University. This project benefited from an Australian Religious History Fellowship at the State Library of NSW and an Australian Research Theology Inc travel grant.

This article is a syndicated news item via ![]()