Image: One of these vases was painted by a woman; the other by a man. Can you guess which is which? B van der Ast/M van Oosterwijck

In the art world, there is a gaping gender imbalance when it comes to male and female artists.

In the National Gallery of Australia, only 25% of the Australian art collection is work by women.

This is far better than the international standard where roughly 90% of all artworks exhibited in major collections are by men. The most expensive painting by a female artist – Georgia O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 – does not even rank among the 100 most expensive paintings ever sold.

Why is women’s art valued so much less than art by men?

Some economists have suggested the greater burden of child rearing and other domestic duties means women have had fewer opportunities to succeed in the art world.

Others have blamed the “quality” of women’s art. In 2013, German painter Georg Baselitz said “Women don’t paint very well. It’s a fact. The market doesn’t lie.”

We wanted to know: is work by women generally valued differently to work by men because it is of a lower artistic quality, or is it just discrimination?

Which painting do you like better?

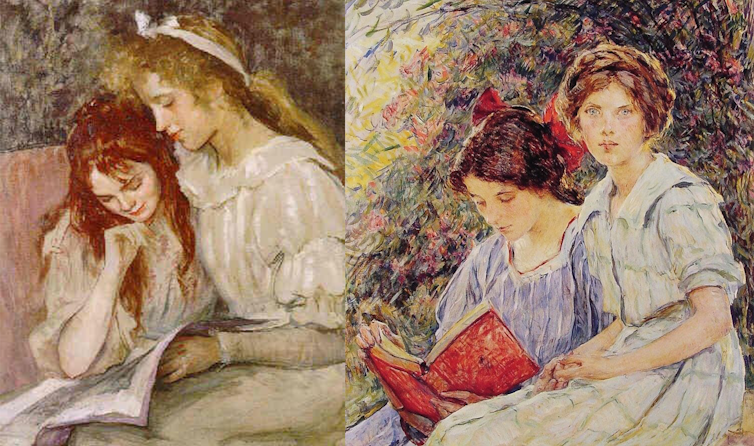

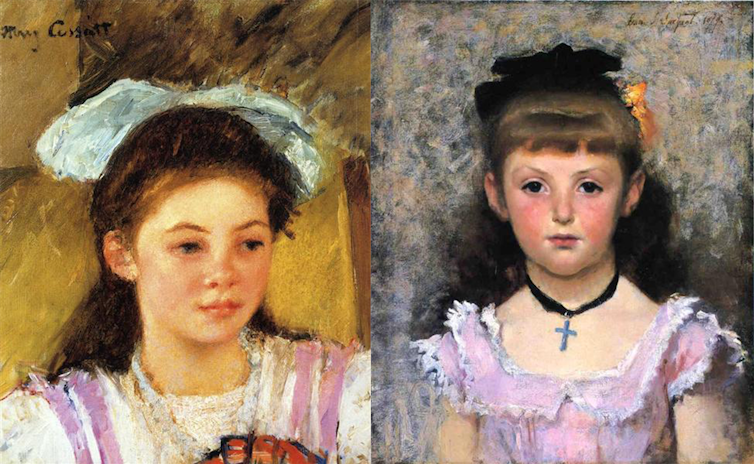

In our new research we showed average Americans pairs of paintings, painted between 1625 and 1979, side by side. Each of the pairs are similar in style, motif and period, but one work was by a male artist and the other by a female artist.

Participants were in two groups. One group saw the artists’ names and the other didn’t. We wanted to see whether more people among those who saw artist names preferred the male painting.

If seeing the names – and thereby inferring artist gender – causes more people to prefer male paintings, then there is gender discrimination.

Before we tell you the results, think about what you would have expected. And take a look at our actual painting pairs and see if you can guess which is the male one (hint: you can’t).

We were pleasantly surprised to find our participants did not give a hoot about artist gender. In both groups, 54% preferred the painting from a woman.

We repeated this experiment, this time rewarding participants if they could accurately guess the preferences of others – the people in the first experiment.

Again, 54% of the people in each group picked the female paintings.

Which painting do you think is worth more?

Next we wanted to find out if people picked male paintings for reasons other than personal taste. Art isn’t just bought and sold on aesthetic value: it is a speculative market, where art is treated as an investment.

We conducted two more experiments. In one, participants were rewarded if they picked the more expensive painting. In the other, they were rewarded to pick the one painted by the more famous artist.

Gender discrimination emerged in both these experiments. When asked to predict the value of and creator fame of paintings, people suddenly swung towards picking male artists. Preference for female paintings fell by 10% and 9% in these two new experiments.

Gender discrimination in art comes not from personal aesthetic preference – Baselitz’ argument that women “don’t paint very well” – but people thinking paintings are more valuable and famous when painted by male artists.

A question of fame

In our fifth experiment, we again rewarded participants who could correctly guess which painting would be preferred by others. This time everyone saw the names of the artists. But only one group was told which of the two artists was objectively more famous – the male artist in 90% of cases.

The group with that information was 14% more likely to pick male paintings. People used fame information to predict the painting others liked better.

If women artists were discriminated against just because of their gender we would have seen a higher premium put on the male artists even in questions of aesthetics.

Here, discrimination only occured when our participants were asked to assign a monetary value to the art works, or when they were given information about the level of fame of the painter.

This means our art appreciators discriminated not on gender, but on something closely associated with gender: fame.

And because male artists have, historically, been given more opportunities to become artists – and therefore become famous – artwork by men is perceived as having a higher value.

Policy is slowly starting to recognise and target institutional factors that perpetuate male dominance because of historical notions of fame, like the National Gallery of Australia’s Know my Name initiative.

Discrimination in the arts exists, but it often comes from people’s beliefs about what others care to discriminate about. The task ahead is to change perceptions of people and institutions who do not discriminate – but merely conform to others’ discrimination.

This article was co-written by:

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article is a syndicated news item via ![]()