Image: Shutterstock

This year’s federal budget is characterised by an avalanche of immediate handouts in response to cost-of-living pressures, some sound initiatives and deferral of more fundamental decisions. This is precisely reflected in how the budget treats energy and climate change.

The A$1 billion to expand Australia’s low emission technology capabilities, such as green hydrogen, is welcome. But cuts to the fuel excise represent poor policy on fiscal and environmental grounds.

From the devastating bushfires of 2019-2020 to this year’s shocking floods, unprecedented climate-related disasters have wrought havoc across Australia.

It is deeply regretful that the budget and forward estimates do not specifically recognise the ongoing, and escalating, scale and the fiscal impact of these disasters.

Fuel excise is poor policy

For six months, the government will halve fuel excise to 22.1 cents per litre to offset soaring petrol prices. This short-term reduction will undoubtedly be welcomed by anyone with a petrol or diesel vehicle, and may provide the sort of political boost the government seeks ahead of the election.

Yet, it is poor fiscal policy. First, the outlook for global oil prices is as unpredictable as the outcome of the Ukraine war. That means the cut in fuel excise will quickly be either too strong a response or insufficient.

Second, restoring the level will not be politically simple. As a relief for households under financial stress, the measure is poorly targeted.

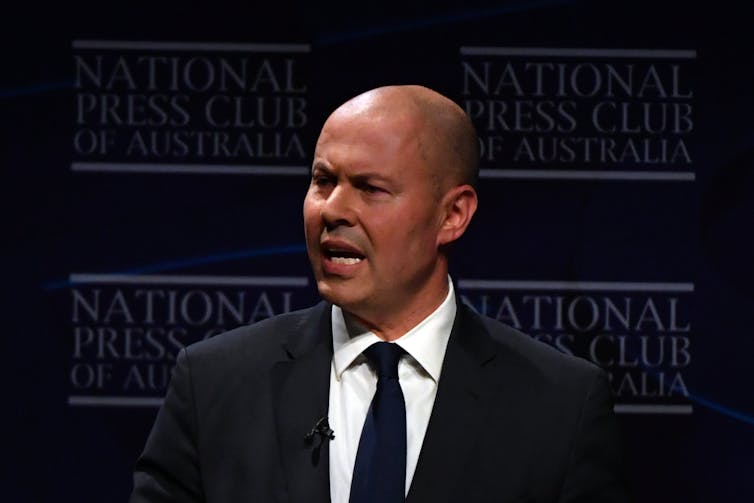

It is also a stark illustration of how motorists today would already be financially better off if Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was able to implement his proposed fuel efficiency standards in 2017, when he was the minister for energy and the environment.

At that time, the benefit to motorists was calculated to be more than $500 per year by 2025 – and that was based on prices below $1.50 per litre, well short of current levels above $2. And of course, we would have been making tangible progress on reducing emissions in the transport sector.

Funding low-emissions technologies

Development and deployment of low-emission technologies – such as clean hydrogen, green steel and carbon capture and storage – will be critical to meeting Australia’s commitment to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

The government’s commitment of more than $1 billion to projects to support these technologies is welcome, as is the allocation of $84 million to support the development of microgrids.

These investments are generally aligned with the government’s technology investment roadmap, released in 2020. However, it would be better for these projects to be selected via an independent agency with criteria set by the government.

The government emphasises a “technology, not taxes” approach to bringing Australia’s emissions to net zero. But funding the net-zero transition from government coffers is not sustainable.

We need policies such as a price on carbon that encourage the market to deploy these technologies at scale. The recent history of such policies in Australia means this will be a big challenge for whoever is energy minister after the looming federal election.

Australia’s extensive renewable energy and critical minerals resources mean we could be a global leader in manufacturing, for instance, downstream processing or iron ore, copper, lithium and similar metals critical in a low emissions world.

So the $1 billion in the budget to boost our manufacturing capability is another step in the right direction.

But again, good governance should include a clear framework that determines which projects get selected. This process should be based primarily on Australia’s potential competitive advantage.

The primary source of such advantage lies in our renewable energy and minerals resources, while specific regions may also have advantages based on existing infrastructure such as ports and skilled workforces.

Investments in low-emission technologies and manufacturing is closely aligned with this budget’s focus on Australia’s regions.

Investment in new opportunities will be welcomed in the regions. It should be accompanied by an equally strong commitment to working with regional communities that may suffer job losses and other economic harms in the transition away from fossil fuel industries.

Short-term climate thinking

Frydenberg’s budget acknowledged the devastation wrought in Australia by floods, drought and bushfires. Yet it failed to acknowledge the future cost of such disasters on the budget under climate change.

The budget includes measures to make regional Australia more resilient, to mitigate the impact of these disasters and support insurance coverage. But these are short-term commitments.

Even if we manage to stop global warming beyond 1.5℃ this century, the frequency and severity of natural disasters will only worsen. Australia is already feeling the damage.

The economic and fiscal consequences of these disasters will only increase. And there will be other risks from a changing climate such as rising health spending and reduced government revenues from key exports, including liquefied natural gas.

So what should the government do differently?

At the very least, the federal government should move to better understand and quantify the fiscal risks from climate change.

First, it should include some of the immediate risks of climate change in the budget’s “Statement of Risks”, which outlines the general fiscal risks that may affect the budget.

Second, it should adjust medium-term fiscal projection models to factor in declining revenue from fossil fuels, higher cost of debt, and higher expenditure on health and natural disaster supports.

Third, the longer-term impacts of climate change on the budget must be modelled. This should inform the next Intergenerational Report in 2025, which provides an economic outlook for Australia over coming decades.

Climate change ultimately challenges governments to reconsider their fiscal strategy. The many climate-related uncertainties make a strong case for preserving fiscal flexibility and firepower to cushion the direct impacts of climate change, including natural disasters.

This article was written by:

Disclosure statement

Through his superannuation fund, Tony Wood owns shares in several companies related to the energy and resources sectors.