Image: Josh Gorringe at the Debney Peace site in 2019. Photo: Tom Griffiths

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and/or images of people who have passed away.

In July 2019, the Queensland Government launched a series of community consultations as part of its Path to Treaty initiative. The then Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships explained that “when Queensland was settled, there was no treaty agreement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first custodians”.

“First Nations peoples,” continued the government statement, “were displaced from their land without any negotiation, resulting in political, economic and social inequalities that continue to this day.” On 11 November 2019, one of 24 public consultations around the state was held in Birdsville in the Channel Country of south-western Queensland.

At the Birdsville meeting to discuss Treaty, Mithaka Elder Betty Gorringe said just one thing from the back of the room: We already had a treaty: the Debney Peace. It’s in Alice’s books.

What was the Debney Peace, when and where was it negotiated, and why is it nationally significant in 21st-century Australia?

And who was Alice?

Harrowing decades of war

In May 1889, after more than two decades of brutal conflict on the Queensland frontier, a five-day peace ceremony was performed on Mithaka Country. It was orchestrated by the Mithaka as part of a traditional regional gathering for initiation ceremonies and drew 500 Aboriginal people from across the Channel Country as well as from the Barcoo and Warrego rivers to the east.

The event became known by settlers as the Debney Peace in honour of the white leaseholder of Monkira Station, George Debney, who helped to organise proceedings. The peace functioned as a negotiated truce in the frontier war, an unwritten agreement solemnised in ritual and ceremony.

On the vast plains of the Channel Country, the Cooper Creek, Diamantina and Georgina rivers flare out into a myriad of braided channels, revealing an intricate web of arteries. It is a boom-and-bust ecosystem, an arid land animated by water flows from elsewhere, a place where monsoonal rain falling hundreds of kilometres away to the north-east periodically floods down dry channels, bringing a spectacular pulse of life to the plains.

The flush of water occasionally reaches all the way to the salt pan of Lake Eyre, a continental rain gauge. More than 500,000 square kilometres in size, the basin is the largest inland draining system in the world. Aboriginal peoples of the region hold up the open palm of their hand to signify the basin; their fingers are the rivers that drain into it.

For tens of thousands of years, people lived in this place. Every tree, rock, dune and channel had a name and a story. Water defined these people. Anthropologist A.P. Elkin said of Aboriginal peoples in the lower Channel Country that

one never asks the name of a person’s camp, ngura, but of his water, kapi. Man is tied from his birth to his death to the rock holes and soaks, and to the tracks between them.

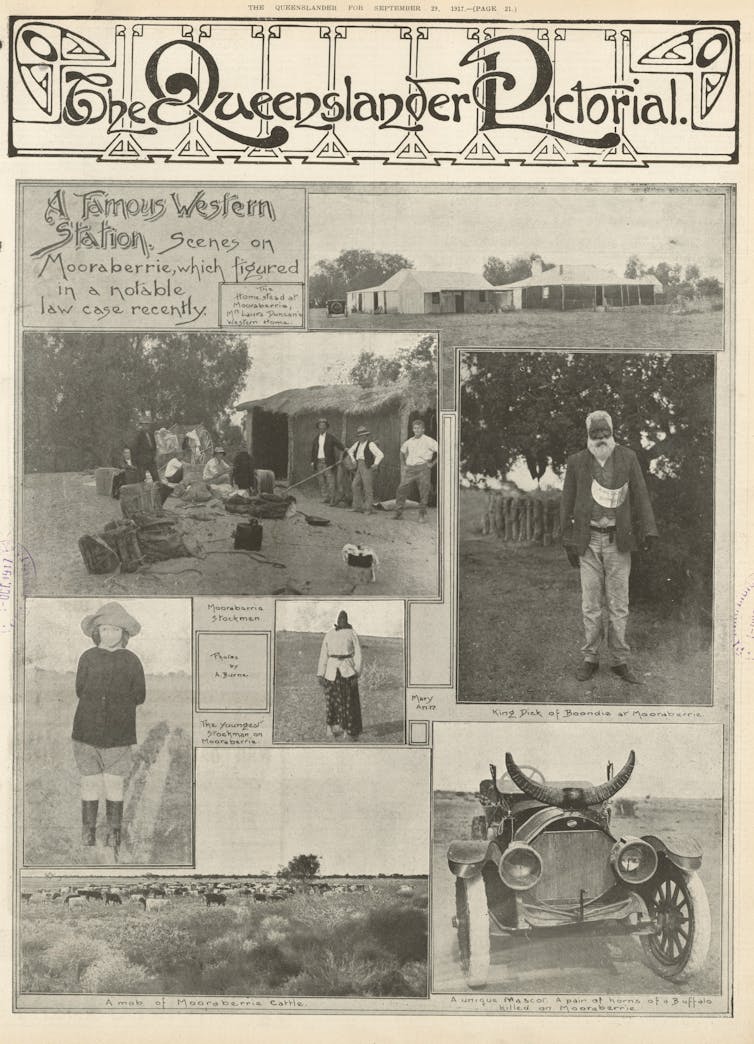

In spite of erratic water, the land sustained permanent habitation. In the early 1900s, after decades of dispossession and war, there were still 13 Aboriginal dialects spoken within 80 kilometres of Mooraberrie, a pastoral station between Windorah and Birdsville.

Journalist George Farwell, in his book Land of Mirage (1950), recorded a settler near Cooper Creek claiming that he used to stand on a hillock and see the flat beyond full of Aboriginal women “as thick as sheep grazing” as they bent over in search of seeds, roots and small bulbs.

This density of population was high for this arid region of Australia, and First Nations peoples lived in communities larger than many outback towns today.

This remote south-western corner of Queensland had been a place of trauma, violence and disruption from the 1860s, accentuated by the ecological extremes. The sheep and cattle of the invading pastoralists destroyed the native grasses and waterholes, and conflict increasingly erupted between Indigenous owners and the newcomers.

By 1875 most of the Diamantina channels were leased to pastoralists and by the early 1880s almost all the Channel Country had been parcelled and claimed for stock. The 1870s and 1880s were harrowing decades of war. There was a long, tense, violent struggle for possession and control of the land and its resources.

First Nations peoples speared cattle and sheep and occasionally killed settlers; the newcomers massacred whole clans in revenge. Mary Durack, whose forebears colonised the Channel Country, wrote that by the mid-1870s

many settlers now openly declared that Western Queensland could only be habitable for whites when the last of the blacks had been killed out – “by bullet or by bait”.

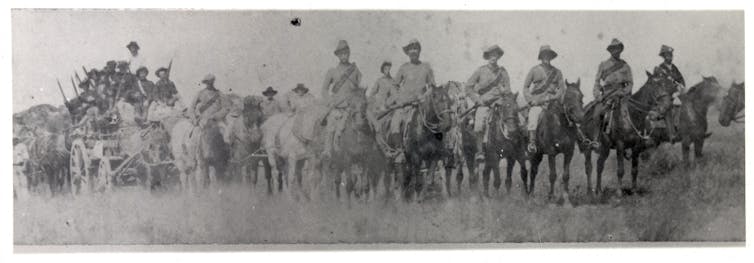

A Native Mounted Police force operated in Queensland for more than 60 years up to 1910 (when, from 1848 to 1859, the area was part of New South Wales, and then a separate colony) and was more lethal than in any other colony.

Historian Jonathan Richards describes this force of mounted Aboriginal troopers led by white officers as a paramilitary organisation, and Raymond Evans calls it a counterinsurgency force. It operated under the direct control of the executive council of the colonial administration and functioned secretively. It was effectively deployed as a death squad.

Although specific frontier violence was shrouded in silence, many colonists were willing, indeed determined, to speak openly both for and against what was going on. “From what has come within my own knowledge I can believe that the atrocities you have published are true in their general statements,” wrote “Outis” to The Queenslander in June 1880. “We must admit that a war of extermination is waging on all sides.”

He accused the Native Police force of committing “wholescale murder”. The strategy of their detachments was to surround Aboriginal settlements and fire into them at dawn, killing men, women and children; they then burnt the evidence of the bodies.

More than a dozen major massacres are known and remembered in the Channel Country. Most began at waterholes where people gathered and lived, often in large numbers. Some were reprisals for the theft of cattle, while others were provoked by the Aboriginal execution of lone white men who raped Black women. The Native Mounted Police were generally involved.

Large ceremonial gatherings were targeted and death tolls from single events could total more than a hundred, even up to 200. The waterholes – the precious jewels of the arid country – were transformed into a grim roll-call of places of death.

Sometimes the conflict seemed to challenge the very possibility of long-term European settlement of the Channel Country. By 1885, leases forfeited were nearly as numerous as runs leased for the first time, and by 1890 fewer than one in five of those who had initially leased runs remained.

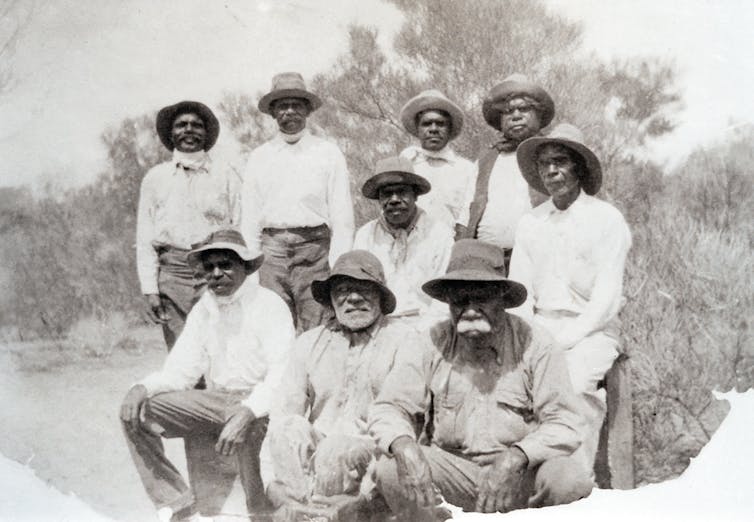

Aboriginal labour had also become essential to the white pastoral economy. As Mithaka survivors dealt with long-term British pastoralism on their lands, they also proved indispensable to the newcomers. Most Channel Country pastoralists could not have stayed on their land without the cheap labour of the locals.

The invading pastoralists, although very strange in many of their customs, had characteristics that were recognisable to the original inhabitants. The whites were nomadic, prized waterholes, had ties of kinship with their white neighbours and ran an economy centred on the management of animals over wide territories.

First Nations peoples often advised where homesteads should be built to avoid periodic flooding, counselled on signs of drought and rain, and knew where to find water. Work on the stations, both pastoral and domestic, relied on them heavily. They were the best riders and horse breakers, proficient at mustering and knew where to seek straying cattle.

But they were paid little or nothing and generally received scant rations of food and clothing instead of wages. They suffered from introduced diseases and the effects of alcohol and opium, and on some stations Black women were coerced into sexual servitude to white workers. The economic and social dependence of remote European pastoralism on unpaid and exploited Aboriginal workers remained long unrecognised in Australian histories.

In remote regions where the land was so vigorously contested and where a cheap Aboriginal workforce underpinned the economy, local agreements were sometimes made between European pastoralists and First Nations peoples.

And occasionally, in attempts to keep wholesale slaughter at bay, broader regional settlements were reached. A negotiated truce – a ceremonial accord – could offer some kind of future for both sides. All of this led to the Debney Peace.

Frontier warfare and vengeance parties

George Leonard Debney (1843–1908) was a tall, bearded man with blue eyes, personal charisma and a dignified bearing. He arrived in the Channel Country about a decade after Patsy Durack and John Costello had established their stations on Cooper Creek. When Debney became managing partner of Monkira Station on the Diamantina in 1879, he already had experience of frontier warfare.

In 1868, following a spate of sheep stealing at Mundowdna Station in north-eastern South Australia, Debney and his partner John Woodforde were involved in what the South Australian Register called a “serious native affray”. After a struggle, the pastoralists shot two Aboriginal men, whose bodies were carried away by their countrymen; the station homestead was burnt to the ground as a retaliatory action.

Lacking bodies of the victims and judging that the white men fired in self-defence, the government did not pursue proceedings. Debney thus had personal insight into the cost of occupation without negotiation. “Where you don’t see any blacks is where they are sure to be and thickest,” he would say.

When Debney and his family arrived to live at Monkira in the early 1880s, they encountered stern resistance from the locals. “The Murranuddas”, as the local Mithaka clan was called, were renowned as a fierce and assertive people and on several occasions they subjected the homestead to siege.

Detachments of Aboriginal warriors, known as the “storm birds” and “dingo men”, conducted guerrilla-style warfare against the pastoralists of the region.

Debney, learning from his earlier experience, became a respected mediator of conflict, helped sick Aboriginal people and was once “an honoured guest of a fierce war-like tribe” when he was injured while mustering alone. It soon became apparent to Debney “that the head men of the tribes would have to be got together”.

Debney had been a Justice of the Peace and a court magistrate in South Australia before coming to the Channel Country, and in 1884 he was sworn in as a JP at Monkira. This meant that he had a formal role as a “protector” of the Aboriginal peoples of his region. By 1887 his acquisition of Monkira was complete and he probably wished to secure its future.

With the help of Barralong, a Monkira stockman, he began two years of consultations with First Nations leaders, including two he had known for many years: Winjan of the Eaglehawks and Knuppa-pip-pa Budgeree of the Wonkamurras.

Debney was worried that further unrest would bring the attention of the Native Mounted Police and that they “would set upon the myalls and shoot them down like wild dogs”. The Mithaka shared his fear: in early 1888, during a “great commotion” at Mooraberrie Station, it was reported that “the blacks here have a wholesome dread of the black troopers”.

The local Native Police force was led by a man of Debney’s age, Robert Kyle Little (1841–1889), an Irishman who had served in the British Army in the Crimean War and established the first Native Police camp on Eyre Creek (the Mulligan River) at Bedourie in the early 1880s.

It was Little who led a vengeance party at Cooninghera Waterhole when the head of a cook was found in a camp oven following the rape of Black women.

As later told to George Farwell and reported in Land of Mirage, Little “chased the whole tribe all over the country, overtaking the first of them six miles from the waterhole, where they were shot out of hand”.

Little killed others at Coongie Lake and more still at Coonchere sandhill. This was the representative of white law with whom George Debney and other Channel Country pastoralists had to work.

The Debney Peace settlement

In May 1888, Senior Inspector Little wrote from Eyre Creek to the commissioner justifying his job on the remote edge of settlement and confirming the Native Mounted Police were “still very much required out here”. He argued that

Should the N.M. Police be removed it would be the old story over again; outrages by the blacks and retaliation from the Squatter.

Inspector Little died suddenly of “sunstroke” or “heat apoplexy” in Birdsville in January 1889. But, according to local oral history, he had already given the nod to Debney’s consultations with Indigenous leaders.

This was crucial, for a successful regional peace depended on the assent of the Native Police. It’s unlikely, however, that Little mentioned the negotiations in official reports (which were, in any case, deliberately destroyed by government in 1939): it was not in his interest to record any “peace settlement”.

His duty was to clear the country. Furthermore, sanctioning such negotiations may have constituted official recognition of a state of war, which would have been unacceptable to the Crown. Nor did pastoralists want to advertise the event, for any willingness to negotiate with the land’s original owners could have suggested weakness – or even acknowledgement of their rights.

To be effective, the Debney Peace needed to be known among First Nations peoples, a select group of local pastoralists and the leadership of the Native Mounted Police. But otherwise it would not be for public report. This is why knowledge of the event survives only in the early oral history recorded “in Alice’s books”.

‘Alice’s books’: a rich ethnographic source

I was 14 when I came across one of “Alice’s books” in a library. The dusty volume was sitting unobtrusively on a shelf of “Australiana”, but it looked different to its companions and immediately attracted me.

Even its title was mysterious: Where Strange Paths Go Down. The book described happy childhood memories of warmth and companionship with Aboriginal women and men at home on their own country. I was drawn into its glowing stories, and the compelling strangeness of the book stayed with me.

Its author, Alice Duncan (later Duncan-Kemp), was born in 1901, the year the Australian colonies federated. She grew up on Mithaka Country. Her parents, William and Laura Duncan, managed the pastoral property known as Mooraberrie on Farrars Creek west of Windorah, where they employed Mithaka men and women at the homestead and in the paddocks. William Duncan (1858–1907) emigrated from Scotland as a young man, worked in western NSW and arrived in the Diamantina in the late 1880s about the time of the Debney Peace.

Knowledge of the agreement may have encouraged him to take on the run: George Debney was a near neighbour and friend. Winjan, the Elder who knew Debney, showed Duncan where he could safely site his homestead. In 1898 Duncan married Laura Davis from Parramatta, the daughter of a Sydney solicitor whose sister had married another neighbouring pastoralist, Allen Alexander of Daroo Station.

As an amateur ethnologist, William was fascinated by the history of human migration and took a strong and sympathetic interest in the people whose lands he had usurped.

Alice remembered that her father believed it to be “an uncontestable fact that Aborigines are the rightful owners” of the land on which they lived, and it was his habit to refer to Mithaka Elders as “the landlords”.

Mithaka people determined which sections of the property were accessible at particular seasons, and when cultural considerations should prevail over pastoral routines; they advised on the life cycle of grasses and forecast the weather. They built the homestead, established the garden, cleaned the house and lived nearby in a settlement by the creek. At grace before dinner the Duncan family gave thanks to “white pioneers, black saviours”.

Alice had an older brother, David (“Poppy”), who died of diphtheria aged four, and two little sisters, Laura and Beatrice. In 1907 her father died prematurely from an illness exacerbated by a fall from his horse. Alice, together with her sisters, was nursed, cared for and tutored by Mithaka people.

She was made welcome at the “kindergartens” of her young Mithaka playmates and absorbed everything they were taught. Soon she was writing it down, for she picked up pen and paper from an early age and always carried a notebook. Young Alice was a gatherer of facts and asked questions endlessly to clarify matters. As an older child she joined mustering journeys for weeks and spent days in the saddle and nights by the campfire listening to the yarning of Elders Black and white.

Her beloved companions and teachers were Mary Ann Coomindah, head of the homestead domestic staff, Moses Yoolpee, a stockman, gardener and tracker with some European schooling, and Bogie, a stockman and rainmaker who had survived a massacre at Kaliduwarry as a teenager in the late 1870s.

‘Twice-born’

Alice’s Mithaka teachers regarded her as “twice-born”. At the age of two, she had survived an accident while crossing the flooded Bulloo River with her father and two Mithaka stockmen. The stockmen, Wooragai (Chookie) and Bogie, struggled to get the buggy and horses (one of which was badly injured) onto dry land before lighting a small fire and beginning a sacred chant.

The Mithaka believed that the accident revealed Alice as a reincarnation of a powerful spirit, the appearance of whom they had been awaiting. When Alice was a little older, her nurse, Mary Ann, took her to Kulkia, a flat-topped hill, where her Mithaka teachers were gathered at a small fire within a circle of white stones.

They inscribed Alice’s forehead with ochre and touched her with the heated stone tip of a naming spear, giving her the name Pinningarra (the Leaf Spirit). She was presented with a small, thin spear made of acacia, pointed at both ends, which Alice treasured. It remains in the Duncan-Kemp family today, a beautiful object. For the rest of her life, Alice bore a faint burn scar on her left breast from the naming ceremony.

Alice grew up with a feeling of deep gratitude, respect and love for her Mithaka teachers. These years of cross-cultural learning were the most important of her life and she spent the next 60 years remembering and celebrating her unusual education. As well as becoming a farmer, wife and mother, Alice (who married Fred Kemp) was a writer – and her subject was the Mithaka people she had known and loved as a child and young woman.

She wrote four books: Our Sandhill Country (1933), Where Strange Paths Go Down (1952), Our Channel Country (1961) and Where Strange Gods Call (1968). A further manuscript, People of the Grey Wind: Life with a Stone Age People, was published posthumously by her family in 2005. All her published writing was autobiographical non-fiction relating to the first 20 years of her life at Mooraberrie.

She had lived in a kind of “wonderland”, a world animated by the parallel universe of Mithaka stories and traditions. In her memoirs, she chose an Aboriginal style of storytelling: “I have always tried to tell and to write things as they themselves would have told it.”

Her narrative style of interwoven journeys and memories, rendered in vivid detail, led many readers and scholars over the years to believe that she was fictionalising her experience and inventing characters and encounters.

As an outback woman – a writer, a sympathiser with Aboriginal spirituality and a pastoralist memorialising the frontier in rather a different way – Alice found that her books could make people uncomfortable or confused. There has been a steady stream of disparagement of her work, from white locals believing that “a bloody woman had no right to be able to get the material” to a senior academic dismissing Alice’s work with hardly a glance at it.

One reviewer labelled her narratives “tall stories”, saying that it was “impossible to take many of them seriously”.

Frontier denialism

In 2018, the commissioned historians of the Barcoo Shire – in a book entitled Their Promised Land – dismissed Alice’s evidence because she was “only a child or a very young woman” when she had her Mithaka education, and added that Aboriginal people were not in any case capable of the kind of defence of Country that Duncan-Kemp described. This is Australian frontier denialism at work.

To accept Alice’s testimony is to confront the tragic scale of the human loss that accompanied violence and dispossession on the Queensland frontier.

There is so much cultural material in Alice’s books that it is easier to dismiss them as “colourful” or “fanciful” than to understand them. The very detail of her account saw people assume she embroidered or imagined it. How could official records describe a people as “miserable, tattered remnants” while this woman remembered a rich cultural and religious life still in existence?

It was possible for both to be true, as anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner found in the Daly River in the 1930s and 1950s, and as is becoming still clearer across the continent through the resilience of Indigenous ceremonial life and belief systems in the face of trauma and dispossession. Duncan-Kemp reveals a violent frontier where cross-cultural learning and compassion were still possible, where there was joy among the darkness. Alice’s books have also attracted champions.

Many contemporaries admired her work – A.P. Elkin, Charles Barrett, Charles Mountford, Nan Chauncy, Olaf Ruhen and Nina Durack, for example. The greatest contemporary tribute came from Dr Lindsey Winterbotham (1887–1960), a doctor of medicine who became the honorary Curator of Anthropology at the University of Queensland. Winterbotham solicited Aboriginal information and artefacts from around the state and corresponded with Alice from 1948 to 1957. He asked her:

Do you realise that the different letters that you have written to me in past times have contained the fullest and most scientific knowledge that I have received from any correspondent?

Dr Winterbotham made Alice a foundation member of the Anthropological Society of Queensland, read her books and asked her questions, to which she replied seriously and at length. He read out her letters at Anthropological Society meetings and submitted her material (under their joint names) for publication in the journal Mankind. Alice’s “scientific” letters to Winterbotham are consistent with the stories in her books.

Scholars who have since looked at Duncan-Kemp’s work in detail – historians Pamela Lukin Watson and Yvette Steinhauer and anthropologists Tony Jefferies and Paul Gorecki – have come away humbled and impressed. Linguist Luise Hercus, at first suspicious of Alice’s unsystematic recording, found herself increasingly respectful of her knowledge.

Alice’s descriptions of plants and animals have won the regard of desert scientists, and she is one of Australia’s most significant and exuberant nature writers, recently celebrated in Luke Stegemann’s Amnesia Road (2021). Crucially, the Federal Court of Australia considered the evidence of her books in its Native Title consent determination for the Mithaka people in 2015.

In my own engagement with the Duncan-Kemp books and papers, I have tested Alice’s stories by seeking parallel sources and have concluded that she rarely invented substantive detail. In other words, she felt a sacred responsibility to record the stories of her Mithaka teachers accurately. Caution in interpreting her work is warranted: Alice did occasionally paraphrase other authors and sometimes drew without acknowledgement on sources beyond her region.

But overwhelmingly, her testimony was from personal experience. I have thus become open to the exciting truthfulness of her memoir – one tinged by innocence and nostalgia and prey to the glitches of memory, but faithfully told. A precious possibility emerges that Alice’s books comprise one of the richest ethnographic sources Australia possesses.

She was an oral historian of both Black and white lore at a time of tragic transformation. She relied on the yarning of homestead visitors as well as the stories of the Mithaka families; she asked questions of everyone and wrote it all down from an early age.

Far from being disadvantaged by her youth, she was given unusual privileges in terms of access and cultural permission and absorbed everything with the enduring clarity of childhood. Her father told local stories at night in the homestead and after his death she had access to his journals, since destroyed by other members of her family.

These were the sources of her account of the Debney Peace and the reasons she could write vividly of an event that took place a dozen years before her birth.

The peace ceremony in detail

In a chapter that occupies ten pages of Our Channel Country, Alice describes The Debney Peace:

Debney, alone and unarmed, guided by an old man of the Eaglehawks, moved silently across to the waterhole and out on to a rising slope of sandstone. Here, screened with a light break of brush-willow boughs, burned a fire, and beside it lay bundles of aboriginal tools and weapons. This was the “peace” place or dhooraba (altar), and the white man stood, as aboriginal etiquette demanded of strangers, a little distance back from the fireside.

The white man stood watching the great Mulka-mukana (peace) ceremony, watched the procession five hundred strong march across the claypan … At the head of the Eaglehawks strode Winjan, and with him came Knuppa-pip-pa Budgeree of the Wonkamurras … There was dead silence as Debney stooped to pluck a lighted brand from the fire and hand it to Knuppa-pip-pa Budgeree, taking his torch in exchange.

Although the pastoralists named the peace after one of their own, it was chiefly orchestrated by First Nations peoples. Alice records the name of the ceremony as “Mulka-mukana, the vow of peace and the seal of goodwill”.

Linguist David Nash believes that the term draws on the Karnic (Eyre Basin) language stems of malka (“mark” or “sign”) and muka (“sleep”) and he regards Alice’s translation as plausible. The ritual was grafted onto an event in the existing Aboriginal calendar, a large five-day gathering for initiation ceremonies.

Debney had to ride 60 miles to participate in it. The ceremony was held not on his station but on a tract of country with special significance for Aboriginal peoples of the region – the “Common Ground” or “neutral territory” of the Pharmaleechie Channel. The location chosen had special status as “a sort of buffer state” or “diplomatic immunity area”, as Alice described it to Dr Winterbotham.

Mithaka stories recorded by Alice tell of this site’s significance as neutral ground in pre-contact times when a council was formed to negotiate ancient tribal rivalries and land was set aside as “a hunting ground and meeting place for all but permanent home to none”.

It was an Indigenous event with few if any European features. There were no documents, signatures or gifts, but there was fire, smoke, singing and stamping, a blaze of torches, an illuminated procession through a natural arch of four great gum trees, an exchange of burning torches, a corroboree and the ritual letting of blood.

The performance featured the sudden arrival of 200 armed men from “a strange tribe” who were solemnly greeted before they circled the fire and laid down their spears. Debney “took their spears and carefully arranged them in order of tribal precedence, each in its correct totemic group”.

In this, the white man played his allocated role. It is likely that the peace festival was as much about relationships between the various First Nations communities as it was about dealing with the white intruders. Debney knew several Aboriginal languages and had long been interested in Indigenous lore about plants and animals, but he was out of his depth that night in the shadows and firelight of the sandhills.

Contemporaries and local historians acknowledged 1889 as a turning point in frontier conflict in the region, seeing it as the year when widespread violence ceased, without mentioning or knowing about the peace.

What if Mithaka people had demanded a written document as well as their traditional verbal and ceremonial formalities? Alice belatedly provided one. Her written record is a significant inscription and reminds us that there may be others out there to be rediscovered.

Treaties and sovereignty

The idea of Treaty goes to the heart of the moral and legal anxieties that underlie the Australian nation. The Debney Peace was not explicitly about sovereignty, or even about land, although its location did recognise and consolidate a specific area of neutrality and safety. It was an unadvertised peace in an undeclared war. The peace was an act of desperation by both parties, designed to save lives and livelihoods. Peace-making was one of the purposes of treaties.

The only documented “treaty” in Australian history – John Batman’s two signed deeds with Kulin peoples at Port Phillip in 1835 – was a private contract quickly disowned by government. Although Batman used the term “treaty” and Aboriginal leaders such as William Barak and William Cooper later reinforced the significance of that word, the 1835 agreements were not prosecuted on behalf of the Crown.

In his book Possession (2009), Bain Attwood beautifully analyses the legal confusion about British sovereignty in relation to Aboriginal peoples, especially in this period, when the Port Phillip Association made their attempt at land purchase and called it a “treaty”.

A government treaty with Indigenous peoples would have had implications for sovereignty and raised questions about whether the frontier was a theatre of war. As Raymond Evans has explained in his forensic histories of the Queensland frontier, declaring war would have meant recognising Indigenous peoples as invaded sovereign peoples rather than as “British subjects” whose resistance could be legally defined as criminal.

But an undeclared war, if pursued secretly, could proceed without regard to the conventions of war. There was no need to respect protocols about prisoners and certainly no place for truces or treaties. In Queensland a secret war was waged until a district could be declared “quiet”.

In this way, the title of Douglas Pike’s history of Australia, The Quiet Continent (1962), published a decade before Aboriginal history made an impact on scholarship, now has a sinister ring to it.

In his recent book, Truth-Telling, Henry Reynolds has argued that when the British chose not to pursue treaty-making in Australia (as they did, for example, in New Zealand and Canada) they laid the ground for a much more violent frontier and brought about many more Indigenous deaths.

Not to consider treaties was, he suggests, a “radical departure from accustomed colonial practice”. It was a policy that generated conditions where tensions could only be relieved by violence and where any accommodations or agreements had to be private and unacknowledged. Reynolds concludes that such agreements probably took place all over the country, but “most of them have been lost to the historical record”.

The Debney Peace joins a long lineage of formal appeals to the invaders since 1788: petitions on bark and paper, parliamentary pilgrimages and performances, Rom ceremonies, respectful pleas, dialogues, conferences, promises, campaigns, statements, reckonings, conciliations and makarratas that have been patiently prosecuted across more than 200 years.

It was distinct in that it sought to put an end to devastating violence, as its name conveys. Colonial conquest did not happen in an instant with the raising of a flag; it was incremental, resisted, sometimes negotiated and forever unfinished.

Visiting Mooraberrie, and Mithaka Country

I first visited Mooraberrie in 2000 and again in 2009, soon after the Kidman pastoral company acquired the property from the Duncans and before the Native Title determination for the Mithaka people in 2015. I was moved to finally see this landscape about which Alice had written so passionately, but I had to look at it out of the corner of my eye. Every historical fact and insight had to be gained against the inclination of the landholders.

Kidman’s managers were suspicious of my interest in First Nations histories. I learnt that the historic pisé homestead built by the Mithaka had recently been bulldozed into the creek, and the homestead collection of Indigenous artefacts had been thrown out. The managers had never heard of Alice, whose family had lived there for more than a century. I later posted them a first edition of Our Sandhill Country for their station collection so that the book could come home again.

When, in 2009, I visited neighbouring Bedourie, I was surprised that the little settlement’s good collection of local books and histories did not include any by Alice Duncan-Kemp. But the omission was national as well as local. In 1987 The Oxford Literary Guide to Australia recognised only one writer from the Channel Country: the drover Barcroft Boake, who visited south-western Queensland for a few months in 1889 and wrote one poem called Where the Dead Men Lie about a desolate, uninhabited wasteland. Duncan-Kemp’s half-million published words on a populated landscape were not mentioned.

In 2019 I made a very different visit to Mooraberrie. I was invited to return by the general manager of the Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation, Josh Gorringe, and this time I was working as part of a research team led by Mithaka people and the archaeologist Michael Westaway of the University of Queensland.

Our aim was to bring Mithaka memories together with ethnographic, historical and archaeological evidence to identify significant story places. It was a joy to be on Country with Mithaka people. They welcomed my questions and we talked constantly of the history of the land. They have fought all their lives to retain and rebuild their connection with it.

I had Alice’s books with me and we talked about them too. One day we investigated a vast stone quarry site, mapped it with drones and walked some of its 15 hectares. There were artefacts as far as I could see, large and small – flakes, cores, blanks, choppers, knives, chips and grind- stones, broken and perfect, stacked up like dry-stone walls metres high, an industrial-scale production site.

Some white locals still explain this stunning feature as the result of “a meteor shower”. But these millstone quarries were part of an “Indigenous Silk Road” – dynamic factories at the centre of a vast transcontinental trade exchanging grindstones for pituri (a plant that is a stimulant), ochre, fibre and resin, songs and dances.

Archaeological work by Michael Westaway and his team is confirming the high-density populations described by Alice and finding signatures of peoples poised between the hyper-productivity of flood years and the lean economy of an otherwise dry, hard land.

On a gentle rise near this quarry were stone arrangements and lines of cobbles where strange paths go down. It is exhilarating to work from book to earth, translating words on the page into features of the landscape. As we walked the strange paths, Michael confided to me: “It’s a bit like Heinrich Schliemann reading the Iliad and finding Troy.”

This was the story of an amateur archaeologist named Schliemann who turned Homer’s Trojan War of legend into material, historical reality in 1871 when, with the Iliad in hand, he went in search of the great sites of the Greek Bronze Age and found Troy. The classical reference beautifully conveys the significance of books in our quest. Like Homer, Alice distilled the oral histories of generations.

One evening at dusk as we sat in a circle in the tall iron farm shed, Michael read aloud Alice’s account of the Debney Peace. I marvelled that her words had returned to this place of origin and that we were commemorating, with Mithaka people, an event that took place 130 years earlier.

The next day Josh Gorringe gunned his four-wheel drive over the red sandhills to the Pharmaleechie Channel in search of the ceremony site. The place we found was where Alice said it would be: a majestic setting with a stone arrangement at the foot of a knoll next to a flat-topped mesa, with a waterhole nearby and a claypan large enough for a gathering of 500.

What took place here on this ancient common ground in the late 19th century left a firm fossil imprint in the drifts of the sandhill country. The Debney Peace made possible the continued presence of Mithaka people on their land in a time of war, created the conditions for cross-cultural conversations on Mooraberrie and enabled the education of young Alice.

Much tragedy and loss followed – people were exploited for labour, ravaged by the influenza pandemic of 1919 and forcibly removed by government in 1901 and 1932. But a diaspora of Mithaka families clung on to Country and won Native Title determination, drawing in part on the rich evidence in Alice’s books, the gift of her beloved teachers.

We stood together there – and stand together in this place today – because the promise of the peace fire was, in this mysterious way, realised.

Author’s note: I would like to thank the Gorringe family, the Duncan-Kemp family, the Debney family and the Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation for their strong support for this research. I also thank Michael Westaway, Trish FitzSimons, Grace Karskens, Tim Rowse, David Nash, Paul Gorecki and David Trigger – and Dawn Duncan-Kemp (1932-2021) for her dedication in preserving the archive of her mother-in-law, Alice.

This essay was originally published in Griffith Review 76 Acts of Reckoning.

Kirrenderri, Heart of the Channel Country, an exhibition on Mithaka history and culture is currently open at the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum and will be touring regional Australia.

This essay was written by:

Disclosure statement

Tom Griffiths does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.