Picture: Albert Perez/AAP

Picture: Albert Perez/AAP

As lockdowns ease in New South Wales, Victoria and the ACT, and people return to work and socialising, many of us will be mixing more with others, even though a section of the community is still unvaccinated.

Many vaccinated people are concerned about the prospect of mixing with unvaccinated people. This mixing might be travelling on trains or at the supermarket initially. But also at family gatherings, or, in NSW at least, at pubs and restaurants when restrictions ease further, slated for December 1.

Some people are wondering, why would a vaccinated person care about the vaccine status of another person?

Briefly, it’s because vaccines reduce the probability of getting infected, which reduces the probability of a vaccinated person infecting someone else. And, despite vaccination providing excellent protection against severe disease, a small proportion of vaccinated people still require ICU care. Therefore some vaccinated people may have a strong preference to mix primarily with other vaccinated people.

But what exactly is the risk of catching COVID from someone who’s unvaccinated?

Read more: Opening up when 80% of eligible adults are vaccinated won’t be ‘safe’ for all Australians

What’s the relative risk?

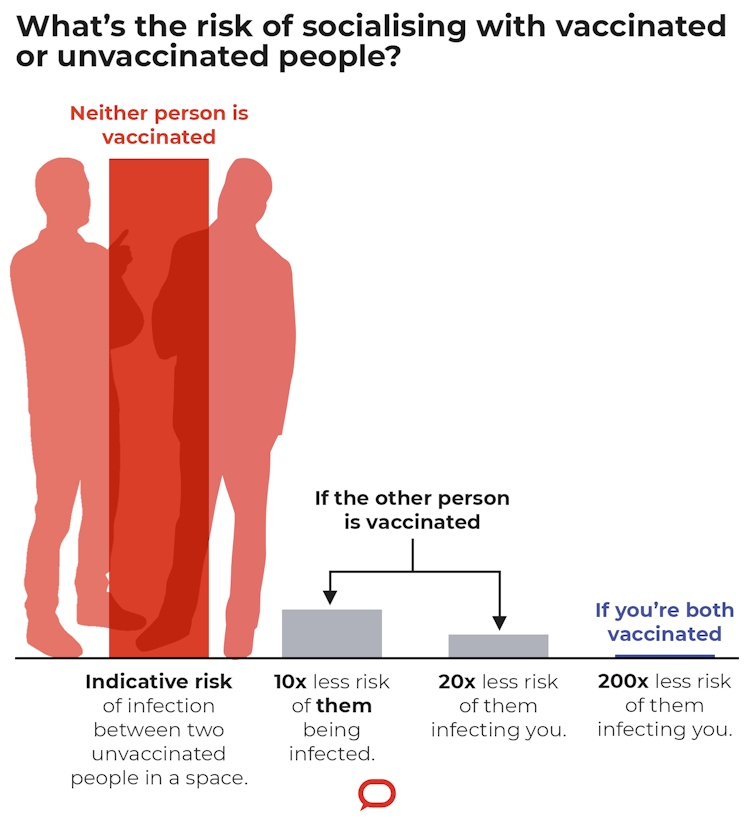

Recent reports from the Victorian Department of Health find that unvaccinated people are ten times more likely to contract COVID than vaccinated people.

We also know that vaccinated people are less likely to transmit the disease even if they become infected. The Doherty modelling from August puts the reduction at around 65%, although more recent research has suggested a lower estimate for AstraZeneca. Hence for this thought experiment, we’ll take a lower value of 50%.

As the prevalence of COVID changes over time, it’s hard to estimate an absolute risk of exposure. So instead, we need to think about risks in a relative sense.

If I were spending time with an unvaccinated person, then there’s some probability they’re infected and will infect me. However, if they were vaccinated, they’re ten times less likely to be infected and half as likely to infect me, following the numbers above.

Hence we arrive at a 20-fold reduction in risk when hanging out with a vaccinated person compared to someone who’s not vaccinated.

The exact number depends on a range of factors, including the type of vaccine and time since vaccination. But, in Australia we can expect a large risk reduction when mixing with fully vaccinated people.

The calculation holds true whether you yourself are vaccinated or not. But being vaccinated provides a ten-fold reduction for yourself, which is on top of the risk reduction that comes from people you’re mixing with being vaccinated.

So, dining in an all-vaccinated restaurant and working in an all-vaccinated workplace presents a much lower infection risk to us as individuals, whether we are vaccinated or not. The risk reduction is around 20-fold, but as individuals, we need to consider whether that’s meaningful for our own circumstances, and for the circumstances of those we visit.

There are also added complexities, in that there are three vaccine brands available, and eligibility is still limited to those aged 12 and older. Although, we do know kids are less susceptible and less likely to show symptoms.

However, as more information emerges, we can always update our estimates and think through the implications on the risk reduction.

What about people who can’t be vaccinated?

Some people haven’t been able to get vaccinated because they’re either too young or they have a medical exemption. Other people are immunocompromised and won’t get the same level of protection from two doses as the rest of the community.

Increasing our coverage across the board will help protect those who aren’t fully protected by vaccination (whether that’s by eligibility, medical reasons or choice).

Those at higher risk also enjoy the risk reduction if they’re able to mix primarily with vaccinated people.

And other choices we make can help reduce the risk of transmission when vaccination is impossible, for example, wearing masks, washing hands carefully, and so on.

Do rapid antigen tests help?

Some people have proposed that frequent testing could be used to suppress COVID spread for those who are unwilling to be vaccinated.

Health minister Greg Hunt said Australians can buy rapid antigen tests from November 1, so they can test themselves at home or before entering certain venues.

So how much does a rapid antigen test reduce risk to others?

To answer that question we need to consider test sensitivity.

Test sensitivity is the probability a rapid test will return a positive result, if the person is infected.

It’s challenging to get an accurate estimate. But rapid antigen tests are about 80% as sensitive as a PCR test, which are the traditional COVID tests we do that get sent off to a lab. The PCR tests themselves are about 80% sensitive when it comes to identifying someone with COVID.

So, if you did a rapid antigen test at home, it’s about 64% likely to pick up that you’re positive, if you did have COVID.

Therefore, rapid antigen tests can find about two-thirds of cases. If you’re going to a gathering where everyone has tested negative on a rapid antigen test, that’s a three-fold reduction in risk.

Even though rapid tests provide a reduction in risk, they don’t replace vaccines.

When used in conjunction with high levels of vaccination, rapid tests would provide improved protection for settings where we’re particularly keen to stop disease spread, such as hospitals and aged care facilities.

Consequently, despite the high efficacy of COVID vaccines, there are still reasons a vaccinated person would prefer to mix with vaccinated people, and avoid mixing with unvaccinated people.

This is particularly true for those at higher risk of severe disease, whether due to age or disability. Their baseline risk will be higher, so a 20-fold reduction in risk is more meaningful.

This article was co-authored by:

Disclosure statement

Christopher Baker receives funding from The Australian Government Departments of Health and Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Andrew Robinson receives funding for biosecurity research from the federal Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment and New Zealand’s Ministry for Primary Industries