Image: Josie Maralngurra touching her hand stencil made when she was around 12. In the background are three white barramundi fish figures with red line-work also created by her father Djimongurr. Photograph by the Pathway project

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

First Nations peoples have lived in north Australia some 65,000 years at least, according to the archaeological evidence. Their history is among the oldest of any in the world. Until recently, though, academics deemed the pasts of Australian Indigenous people did not really count as history. These pasts were of some other quality, they were not the kind that determined world events and shaped the future.

It might seem strange today for some peoples’ pasts to consist only of “myth” or “memory” but others to have the dignity of “history”.’ But when the academic disciplines we know today were taking shape, writing became the dividing line between whose pasts were studied by which academic experts. The historians took writing. Archaeologists took the rest.

In a way, this division made sense, at least from the perspective of European scholars. The study of written records held in an archive requires one kind of expertise, the study of material culture requires another.

The written record was the domain of historians, and whatever came before writing fell to archaeologists. Historians called their times “history”, and archaeologists (except for “historical archaeologists”) studied the newly-coined “prehistory”.

“Prehistory” covered the entire human past up until Mesopotamians started writing things down, about 5,200 years ago. After that, it gets complicated, as different peoples in different parts of the world adopted written literacies, or not, at various times. “History” had different start dates, depending on the particularities of whether and why people wrote, or encountered others who wrote about them.

Of course, this implicitly meant, for many peoples, that “history” began when European colonisers arrived, bringing their writing with them. And so cultures that used literacies other than written script to know their pasts – oral traditions, art and song – were mistakenly deemed not to have history at all.

Archives on stone

Australia’s First Nations people have been saying, quite clearly, repeatedly and for some time, that they do have archives. For many reasons, colonial archives have not been welcoming or accessible to many Indigenous people (although they are now being reclaimed and repatriated by Indigenous communities).

But First Nations people have their own vast repositories of knowledge of the past, if only more historians cared to listen and understand them as such. One such record is rock art.

As Carol Chong (Wakaman), once declared:

Rock art is our record and our keeping place of our knowledge, lore and culture. Rock art is a powerful link between our country, our past and our people.

Patrick Lamilami (Maung) has similarly reported:

Our rock art sites are like history books to us that have stories to pass on to future generations.

Rock art comes in many forms. Some was left by Creative Beings, like the Wandjina in the Kimberley. Most was created by the Old People, the Ancestors. As documents created by observers of happenings, rock art provides evidence about the past. The stunning galleries of art, curated and preserved in rock shelters or across plateaus are therefore also archives. They are collections of records, selectively produced, preserved and maintained.

This archive has its own creators, curators and interpreters, playing a role in the keeping of memory for the community. It can be “read” by those who understand such a text. Like a written archive, it reflects the interests and concerns of that community.

History on the rock – Quilp’s horse

Of course, rock art is not the only archive holding records of long Aboriginal pasts. It is only a surface manifestation of the richer archive that is Country itself. The landscape holds the song-lines and stories of the continent. Rock art simply makes this deeper record visible. Indeed, some rock art is itself a manifestation of the Ancestors.

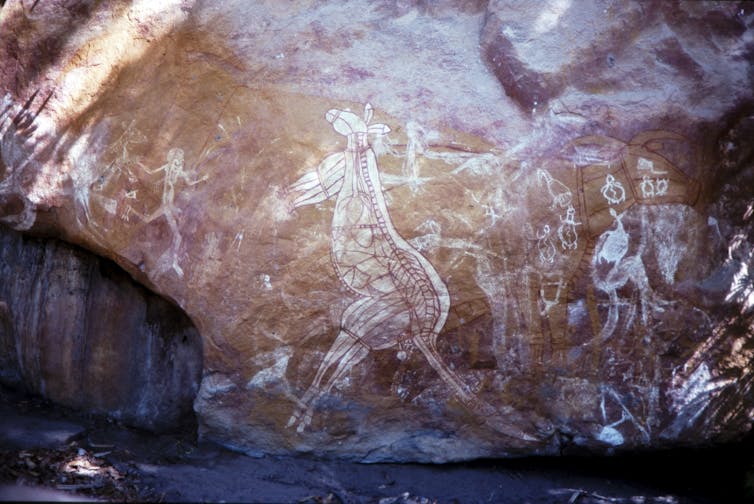

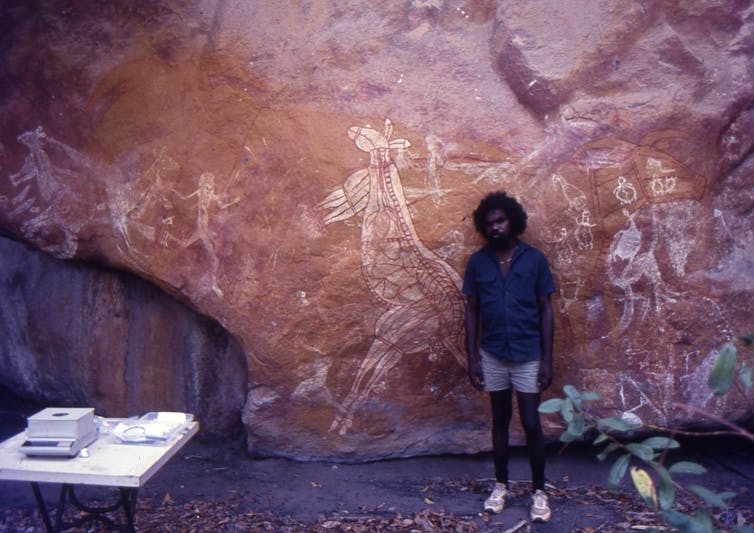

Our forthcoming book is about understanding rock art as an archive, a source of historical knowledge. So, for example, we take this painting near to the Gunbalanya community as a source.

The artist depicted a delicate, light riding horse rather than a heavy working horse. You can see the convex bridge of the horse’s nose and the long head. The carefully outlined eyes and ears give an intimate feeling. This is not a generic horse, but a known horse. The position of the ears may indicate that it is listening backwards, maybe paying attention to her rider.

The western Arnhem Land community knows and remembers the artist who painted this work: Quilp. He was a Wardaman man, kidnapped by buffalo-shooter Paddy Cahill as a boy after his family was massacred, and taken to west Arnhem. He survived and persisted through the violent colonial period because he was good with horses.

When the rock art is read alongside the colonial archive, with an attentiveness to the presence of horses in the artists’ life, we see a story emerge of Aboriginal people using the colonisers’ animals to carve out opportunities for themselves. We see an affinity, even an intimacy with the strange new beasts, together navigating relationships with the “white boss”, as a form of resilience and, in Quilp’s case, survival.

Reading rock art is not without challenges. Like other complex and sophisticated sources, it requires cultural expertise. Rock art, ultimately, can never fully be “read” and understood without the guidance and permission of its owners, and outsiders could never presume to be the experts. Consider this buffalo painted at Djarrng in west Arnhem Land, for instance.

Timorese water buffalo arrived in Arnhem Land in the mid 19th century after the British brought them to their settlements on the Cobourg Peninsula and Melville Island. When their poorly planned settlements collapsed, they left, releasing buffalo, which quickly multiplied.

For the historian interested in Aboriginal records of the past, it is tempting to read the paintings of the buffalo as a depiction of what was supposedly a disruptive and singular event: the release of the buffalo and their expansion through Aboriginal lands. Could we not assume that an encounter with these beasts provoked Aboriginal artists to record what must have been a bewildering experience?

But those who can read the paintings will tell you something else. Traditional owners see the yellow colour and understand that the artist was expressing belonging in their kinship system; the yellow meant the Yirridjdja moiety.

Yellow ochre itself is the transformed bodily fat of Yirridjdja Ancestral Beings, imbuing the painting with power. So the buffalos are not presented as intruding newcomers to Country. Rather, they are revealed as already embedded in Indigenous ways of relating to Country. The rock art is evidence of a history, but it is not the story one might expect.

Some art is even invisible. Two Leg Rock in Kakadu National Park is shaped like a pair of human legs. At its pelvis, over the right hip, there is a painting of an important Ancestral Being in the form of a kangaroo. The painting is depicted in bright, stark white pigment – delek. But visitors to Two Leg Rock today will not see it.

Exposed as it was to the elements – with monsoonal rain passing every year – the painting has faded altogether. But the painting is not gone. Those who can “read” and understand the archive that is the rock art of western Arnhem Land assure us that it remains as present as it was the day Billy Miargu traced its outline in 1972.

This hidden painting exists in a different kind of time to that of the researchers who charted its linear lifespan of creation and subsequent fading away. Many First Nations people experience and relate to time in different and more complex ways than the linear time assumed by academic disciplines. Rock art exists in times that are unchanging, permanent and always alive and active in the present. This is not the chronology of western archives.

Transcending academic concepts of time

The western process of archiving presumes a linear notion of time in its record-keeping practices. Documents are said to progress through a “lifecycle”. The metaphor is cyclical but the concept assumes linearity; there is no rebirth in this cycle.

The documents move from their initial use for which they were created and either transform into “records” as they enter the archive or are destroyed. The creation of the document is disconnected from its use as a record. The researcher is always temporally disconnected from that which they seek to know.

The disciplines of history and archaeology, likewise, presume this kind of time. Archaeology is interested in origins and history, of charting “developments” and “innovation”, “cultural evolution” along a linear timescale.

Academic history, likewise, presumes the times of historicism, where historical “developments” – with cause leading to effect – occur over a linear timeline that is both uniform and universal. Any event in the world can, supposedly, be plotted onto this timeline, like pearls on a string.

Settler observations of the unique Indigenous articulations and ways-of-being in time has led some to conclude that Australia’s First Nations cultures are “timeless”. That is, Indigenous relationships with time supposedly exclude the possibility of a cultural self-awareness that might be called an “historical consciousness”. Such ideas have been grounds on which Indigenous knowledges of the past were excised from “history” and labelled “myth”.

But this is not how Traditional Owners describe and experience time, nor the relationship of rock art to time. The rock art is not timeless but rather connects time, drawing the generations and Ancestors together. They insist that this is history on the rocks, not simply “tradition” or “myth”.

As Wergaia Traditional Owner Ron Marks explains:

Here, this is our library – this is our art gallery. It warms the heart to know that for thousands of years – stories have been written on rock.

Sharing knowledge across generations

Josie Maralngurra, (see lead photo), is not a rock art artist herself. Nonetheless, her life story reveals the multilayered ways in which rock art is a “vehicle of memory” and touchstone of her community’s profound historical consciousness.

Josie was born in 1952 in the “bush” (that is, not at a mission or settlement). Her father, Old Nym Djimongurr, was working for buffalo shooters in what today is Kakadu National Park. In the 1950s, when Maralngurra was little, the family worked at Russ Jones’ Arnhem Timber Camp. Maralngurra was also close to the famous rock art artist Nayombolmi, and called him grandfather.

Maralngurra and her family, along with Nayombolmi and his wife, walked Country throughout her childhood. When not staying in stringy-bark huts, they took shelter in the rocks. Maralngurra described her father and grandfather’s habitual painting in rock shelters where the family stayed.

The men “wanted to sit and do paintings all the time,” she said. Painting was part of daily life in the wet season when the family camped in rock shelters. As a child, she witnessed the creation of rock art across numerous sites.

Today, Maralngurra still remembers these journeys and the painting. She tells of when her family visited these sites, how old she was and where she slept. She can remember who came with them, how long they stayed, what they ate. She remembers the details and stories associated with the rock art.

Children like Maralngurra were often present at the creation of rock art. Sometimes they worked to prepare the pigments themselves. Sometimes the process of painting was their entertainment. Maralngurra tells of her work grinding pigment and gathering food and water.

As she helped the old men, she asked them to tell her the stories of their artworks. So she learned the stories of Country, the Ancestors and their exploits, as well as the protocols of how she and her kin must live today. The process of creation of the artwork was her education.

According to traditional western understandings of archives, they should ideally be “by-products” of human activity. That is, they should not be created with their future as a record in mind. It is this unselfconsciousness that enables them to provide rich evidence for past human activity – they are documents created without thought to influencing future historians.

Although it might be assumed that Aboriginal rock art is often created to record events for posterity, that is not often its main function.

Much of the rock art at Kakadu is the residue of education and knowledge sharing. It is also evidence of how Josie’s ancestors passed the time, telling stories as they painted. Some paintings were originally ways for artists to develop their technical skills. Some were painted simply for fun. Other art was created in a ritual context and may be the remains of ceremonial secret knowledge. Either way, the art at Kakadu was created primarily for its immediate uses.

Yet some of the art is future-oriented, created with the express purpose of embedding memory. Sometimes, for instance, the very bodies of children like Maralngurra were represented on the rocks. In some places, Maralngurra’s own hands joined the painting on the rocks. The outline of her child-sized hands are there, along with those of others. They were created by her father Djimongurr by blowing delek – white pigment – onto her hand and rock, leaving a negative shadow print of her hand on the panel.

Hand stencils are present in rock art around the world. Sometimes they were made to record one’s connection to the place, sometimes they are like a signature, “signing the land”. Sometimes they have been altered to form memorials for people who have died. Sometimes they are located in hard to reach places; surely evidence of the agility and daring of the artist. Whatever their intent, they declare to generations thereafter, “we were here”.

Literally embodying the rocks drew connections between people and landscape, emphasising belonging, and preparing children for their future responsibilities. One generation’s hand-stencils are later witnessed by those to come.

Maralngurra’s life history and experience – the memory of placing her hands on the rockface as a little girl – was inscribed into the landscape, becoming a touchstone for memory.

Rock art is invaluable as an archive for a First Nations history that stretches back millennia. Until now, however, it has not been recognised as such, at least, by non-Indigenous scholars. That is because this Aboriginal archive is a different kind of repository, for a different kind of history, grounded in a different kind of time than the limited pasts many Australians (and academics) are used to knowing.

By their very nature, and by design, these repositories can only be read by and with Traditional Owners to guide. So much the better. We hope that by seeing history on the rocks, history itself might become ever richer.

This essay is the result of a collaboration between:

Disclosure statement

Laura Rademaker receives funding from the Australian Research Council. This research was supported by Ann McGrath’s ARC Laureate (FL170100121).

Joakim Goldhahn receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Rock Art Australia (https://rockartaustralia.org.au/).

Paul S.C.Taçon receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC). This research was funded as part of an ARC Laureate Fellowship (FL160100123).

Sally K. May receives funding from the Australian Research Council. This research was supported by Parks Australia (Kakadu).

Mr Gabriel Maralngurra and Mr Kenneth Mangiru do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.